- Home

- Mridula Behari

Padmini Page 4

Padmini Read online

Page 4

The entire mountain range is gleaming with a golden halo . . . The dark green cloud-shaped trees are shining in the soft sunlight. In the clear blue sky, a few balls of light clouds are floating over green fields. In the valley, the spire of a temple peeps out from behind thickets of trees and bushes.

A squeaky clean white temple, dark and deep woods, wide fertile fields, all bask in the saffron sunlight. The earth looks fresh, as though it had been bathed in molten gold.

She was overtaken by a sense of awe for the beauty her eyes were feasting on.

She continued to gaze at the mountain range, submerged in the shadowy world between dream and wakefulness.

‘Padma! That is the Aravali range. Do you know what the word “Aravali” means?’

She turned towards her husband, who lay on the bed with his elbow resting on a round bolster. A sense of contentment was visible on his face. Dressed in scented silk, he looked relaxed.

She felt a surge of happiness and smiled at him softly. In response, a gracious smile flashed on the king’s lips, lighting up his face. Suddenly nothing was important. Only him. The memory of the previous night made her blush. With her spirits soaring, she stood there, uncertain if she should walk back to him or stay there at the window with an open view to the world outside and her world inside.

They gazed at each other, unable to speak. Then, full of emotion, he said, ‘You are special to me. Believe me, I feel as if I have known you for forever.’

The room was now suffused with bright sunlight. Delighted, she said shyly, ‘Aravali.’

‘Yes,’ he laughed. ‘Aravali means rugged and craggy landscape.’

So drawn was she to him that she didn’t realize she had walked back, still gazing at him. Ratan Singh, too, unable to take his eyes off her for even a minute, said, ‘You have made nature as a whole, its flora and fauna, so very attractive. They, along with you, have assumed a new look.’

There was a curiosity in Padmini’s eyes, which Ratan Singh had no difficulty reading.

Not knowing what else to say, he continued, ‘During the Mahabharat era, Bhim, the son of Pandu, got this fort constructed. Many, many years later, the Maurya king Chitrak renovated it and gave it its new name, Chitrakoot. Now, it is known as Chittor. In the ancient texts, it has been called Madhyamika.’

Padmini listened to him attentively.

‘With the passage of time, our ancestor from the Guhil dynasty, Bapa Rawal, established his kingdom there. A siddha sage named Harit Muni blessed him and said that he would lay the foundations of the biggest empire in Aryavart. Inspired by Harit Muni, Bapa Rawal became a devotee and worshipper of Lord Eklingji. Even today, Lord Eklingji is our family deity. Bapa was a brave warrior. He had defeated invaders coming from the Sindh side. That’s why he is called “the Sun of the Hindus”. Even today, Chittor is a unique land of the brave.’

Padmini soaked in all the information and looked at him eagerly, wishing to hear more.

‘You can call Likhvanbai to your room and seek more information. She knows a lot about this royal family and its history,’ responded the king, reading her expression correctly.

He placed his hand on his bride’s shoulder and raised himself. Then, changing into his long royal robes, he left the room.

After he left, Padmini moved languidly and looked at the paintings on the wall. She stopped in front of one, considering it unblinkingly.

The painting was that of an extremely beautiful woman as comely as Rati, fair with large eyes, dressed in a red corset, a white odhani over her head, and a golden ghaghra covering her waist downward. At the centre was a golden temple of Lord Shiva with a white shivalinga inside. Facing the sanctum sanctorum, the woman—the nayika or heroine—was seated on a giant lotus flower paying obeisance to Lord Shiva by clapping her hands.

Just like the music Padmini had been privy to, the painting drew her into mystic sensuousness. Padmini was lost in wandering thoughts and wayward emotions . . .

* * *

All notes of the melodious music lay dead on the quivering strings of the sarangi. The visage of the king, etched in her heart and mind, stayed intact. But the mirthful nights, still intoxicated by the opulent past, were lost in the desert of stark reality like footprints on shifting sand.

The trees and flowers swaying in the breeze, the sweet smell of freshly wet earth, those days of seemingly everlasting togetherness—Padmini felt it was all a recollection from another life.

Change is the only thing that is constant. Every second was a timekeeper to the change that took place each moment. Just now there was the blush of daybreak on the horizon. And now, suddenly, the sky had again turned into a battleground of ominous clouds.

Extreme attachment to anybody finally leads to extreme indifference. The king’s behaviour towards Padmini was no longer as warm as it used to be. His cold indifference was obvious to her. A man’s attraction to a woman’s beauty is perhaps just infatuation that turns into disenchantment with the passage of time.

A question, as sharp as a spear, pierced her. What if I am handed over to the sultan?

They call the women’s apartment a harem. It is virtually hell, where women are kept as prisoners. Eunuchs and slave girls stand guard over them, and the sultan, suspicious by nature, comes to check his women’s faithfulness. An inhuman life of unimaginable suffering.

Thoughts that portended a frightening future rendered her breathless. A feeling of foreboding weighed heavily on her, creating a disquieting stillness like the lull before a storm.

Quickly climbing the stairs, Sugna ran up to her. ‘His Majesty, our annadata, is coming,’ she panted. Out of breath, Sugna was a picture of nervousness; as if she knew that something ominous was in the offing. There was unusual commotion in every part of Padmini Mahal.

Padmini’s heart began to pound as though it would jump out of her chest. Her bloodstream seemed to have changed its course. A strange restlessness took over her.

Then there was an announcement:

‘Prithvi Raj Raj-Rajeshwhar Maharawal Ratan Singh is arriving!’

A few moments later, the maharawal walked in, his spine erect. Yet Padmini could detect the heaviness in his steps. Her heart sank. An unusual seriousness darkened his face. It was as if she had never seen him before. Who was this stranger? Padmini felt as if her life was hanging from a gibbet. Her mind went blank. She stared senselessly into space. She shifted by looking searchingly into his eyes, as if trying to read his mind. His expression was blank, unreadable. She kept trying to get him to look at her, to reach out to him wordlessly.

He kept avoiding her eyes.

Slowly, he came to the bed and sat on it, leaning on a bolster. He closed his eyes and remained still like one deep in meditation. It seemed as though he was, at that moment, battling a war of thoughts. What was it? Was it about the glorious past? Or was it about their grim future?

She walked up to him noiselessly and placed her hand on his shoulder. He opened his eyes as though he had come out of reverie. She looked at him again, cajoling him wordlessly with her eyes, seeking an answer.

For quite some time not a word was spoken.

‘Why don’t you say something?’

Her gentle query only made him more restless. Beads of perspiration appeared on his forehead. His lips were dry. He stared at her without speaking. A mysterious void showed in his eyes. He seemed to retreat again into an abyss of thoughtlessness.

‘What happened in today’s . . . ?’ She couldn’t bring herself to complete the question. Yet she had to prise out of him what had happened. What was the sentence against her? What was the decision?

‘There’s so much to say. But in an effort to tell you all, I won’t be able to tell you anything,’ he said. His voice sounded dry and distant. His face was as fathomless as a stone image behind a wisp of smoke.

A storm of emotions erupted in Padmini’s mind. Sheer fright engulfed her. That and anger. Today she was not his ‘Padme’, his beloved, his sweetheart, or his s

oulmate, as he dotingly called her. What is making him feel guilty? What is going on that he’s not able to share with me?

She trembled, fearing an ill omen. Once again, she searched his face, hoping to find an answer. He closed his eyes again and turned inward, self-absorbed and tormented. ‘What is it that is preying on your mind, Rajan?’ she asked in a low voice. He came out of his deep thoughts. ‘Well,’ he began, ‘I don’t quite know how to say it to you. It is not always easy to say the truth. At this moment, I am not in a stable state of mind.’

There was no enthusiasm or energy left in him. He was speechless, as though his ego was reproaching him, ripping his existence to shreds. All this only made Padmini more nervous. Her palms started to sweat. She began to feel a strange sensation in her legs.

‘What is it that you can’t find words for?’

Maharawal Ratan Singh was silent for a moment. Then he turned towards a wall and said, ‘That devil Ala-ud-Din has desired to see you once. Not in person but through a mirror. After he has seen your reflection, he will go back with his contingent of soldiers.’

She was speechless. The words were out. There it was, the monster desire, in words. A sharp thorn pierced her heart. It made a tiny tear that grew, ragged and shredded her until she felt that it would kill her. Her face, usually as lovely as the lily flower, turned ashen, as if she had been visited by the shadow of death.

His words swirled around her. The king sat in deep despair, his head lowered, his insides churned up, as if the words that came out of him were not his. He sat still. He may have looked cast in stone, but his anguish was poisonous acid, eroding everything it touched.

Her mind stopped working. It felt as if some venomous substance was seeping into her blood. An excruciating pain ran through her body, leaving her mind numb. Time stood still. And then it passed. Her first words were raw with emotion. ‘Rajan!’ she uttered. She cast a line. Would he pick it up and reel her in? Would he rescue her?

‘Huh?’ He responded in a painful drawl and then kept quiet. He ran his hand over the bedspread. His wavering thoughts would not allow him to concentrate.

‘How can you trust him? What if he does not go back after that?’

He broke his silence. ‘No. He has given it in writing, in his royal edict, that in accordance with the agreement, and according to the holy order, this condition shall be implemented.’

‘Don’t you think it is a virtual surrender of Mewar?’ She fixed her imploring eyes on his face, attempting to read his mind.

‘I am aware of all aspects of the situation,’ he said in an indifferent and slightly harsh tone.

‘So, I have to . . . ?’ Again, she couldn’t bring herself to complete the sentence.

He kept quiet. But the question was hanging in the air, awaiting a reply.

Padmini’s silence became an eloquent expression of her pent-up frustration. She waited. He could not, would not, respond. His silence led to anger welling up inside her. ‘This will bring disgrace not only to me but to all of Mewar.’

He continued to stare into the distance. What was it that he could see and she couldn’t, she wondered bitterly. She had, all along, been dreaming of living a life of self-respect. A queen. Is this what is delivered to queens? Her agitated mind began to revolt. When words become powerless, it is the eyes that say a lot. Ratan Singh saw something in his wife’s eyes, which incensed him. He flew into a rage, ‘Mewar is torn asunder and the Rawal king sitting on its throne remains a mute spectator. Is that what you want?’

But his voice lacked his natural self-assurance. There was no concern for dignity. His valour had dried up. The image of her husband as a fearless warrior and self-respecting king, which she had so assiduously preserved in her heart, was unceremoniously shattered.

His fingers are moving involuntarily. In his heart of hearts he knows that what is happening is not proper. What is wrong with him? Why is he unable to listen to his conscience? Why isn’t he astonished at what has become of him? He is a king. He can fight a battle, lead his armies, challenge the enemy. After all, this is not the first time that he has had to face an enemy’s invasion or a full-fledged war. Then why, oh why, is he becoming weak, powerless, self-pitying?

Padmini had nothing to say. It felt like hundreds of scorpions were stinging her at the same time. Her mind was filled with anger and revulsion for the king. He had lost his manliness, she felt. And what had happened to his pride? She took a deep breath and stood up. There was no point in sitting at his feet. There was no saviour here. She was being held ransom, and the head of an empire felt helpless enough to bow to it. She felt sucked into the endless darkness that was permeating her soul.

The tide of Ratan Singh’s emotions abated. In a flash, all his anger turned into piteous helplessness. He looked at his silently angry wife ingratiatingly, held her hands, and pulled her towards him. He said, ‘Padme! I cannot change the course of destiny. Life is not only that which we yearn for. At times, some things that we cannot imagine in our wildest dreams happen.’

The tone of his voice had touched the apex of self-pity and was about to melt, as though he was unable to find words to express his agony, as though he was hurtling deep down into an abyss in search of some truth.

‘I’ve been ceaselessly fighting with myself. But now it seems I have lost sense and direction. I know I am forcing you into doing something improper and, thus, committing a sin. But what am I to do? I’m shell-shocked myself.’

It was all that he could manage to say, almost as if he were reproaching himself and questioning his manliness. He had been reduced to being guilt-ridden and despondent. Aggressiveness of thought and action had taken leave of him. His sensitive mind, caught in the fierce fight between the force of circumstances and the sense of righteousness, had become perturbed and unsteady. Exhausted to the core, he seemed to have turned inwards, looking for something.

‘Had that impious sultan demanded gems and jewellery, elephants, horses or any material wealth, I would have readily given him all. But that devil has the audacity to eye our Ranivas, the queens’ apartment, a repository of our honour. Tell me, Padme, how can the royal Guhil dynasty accept this?’

Never before had he been lowered in his own eyes. Padmini had never seen him so miserable. He had lost his natural effulgence. He seemed emptied, as if scooped out of his core, unable to rise to the occasion in this hour of crisis. He was lying motionless. Tears flowed from the corners of his eyes. He placed his trembling hand on Padmini’s.

Female attendants appeared at the doorway. The king sat up. They began to prepare for the meal. They mopped the square marble floor that was patterned like a chessboard. A sheet of white linen was spread, on which they placed a bajot, a six-legged hexagonal chowki. Attendants rushed around to serve the king and his consort. A large gold thaal was placed on the bajot and a shat-rasa meal—dishes of all six flavours were served.

The king opened his eyes slowly. He didn’t feel like eating. ‘I have no appetite,’ he said.

Padmini was filled with anger and resentment, but for now she wanted him to eat his fill. ‘All day you have been busy meeting your council of ministers and advisers. You didn’t eat anything.’ Persuasively, she requested him to eat.

Without saying a word, he unwillingly pushed a few morsels into his mouth, out of respect for the god of food. He sipped water from the palm of his hand, rinsed his mouth briefly, and got up. Deterred by his stern visage, she didn’t feel encouraged to say anything. That he showed unwillingness to eat was not unexpected. Ever since the fort had been besieged, he would eat just a little as a formality.

Earlier, when he would sit down to eat, he would invariably offer her a bowl from his plate, asking her to partake of it as a gesture of love and respect. It was much later that she learnt about the gesture being in accordance with tradition. Today, none of that had happened.

She offered him a tambul, a betel leaf, mixed with a crystal of camphor and covered with gold foil. He kept it aside instead of eatin

g it.

The attendants took away the thaal. The linen, the bajot, the serving bowls, the vessels and the ewers were deftly removed too.

Chand brought in the jug of wine and metal cups, arranged them on a table and left. Padmini closed the door and sat close to the king.

Both of them were lost in thought, as though the sources from which their conversations flowed had dried up. Ratan Singh appeared to be physically and mentally disturbed. It was with great difficulty that he kept his emotions reined in. With his eyes closed, he kept lying on the opulent bed. Soon enough, he returned to the tangled web of his problems. At his wits’ end, he downed tumbler after tumbler of wine in order to drown his mental agony and soothe his tormented conscience.

Chand had made the liquor very strong. Soon, the king was lost to the world.

Padmini’s mind was a storm. How could he have taken the stand he did? She had tried to prevail upon him, but he would not listen. As soon as she would try to strike a conversation, he would either pick up the cup to drink or look the other way.

He continued to drink late into the night. His eyelids began to droop. Intoxicated, he pulled his beloved wife towards him and said, ‘My love, I know you are angry with me. Please do not sit so sad and sullen. My most beautiful wife! This world, this life, is to be enjoyed. Come, take a swig or two of this wine. No, no, this is not wine. This is the elixir of life, a divine potion, which will satiate all your desires. What is life if not satiation of desires?’

His contrived jovial tone, however, could not bring any glint of mirth to his eyes. On the contrary, the streak of gloom in them deepened. The forced smile on his lips seemed to have emerged from a blind well. He managed to hold his beloved wife’s chin, raised it slightly and looked into her eyes. All he could see was a blind path, desolate and deserted.

‘Why do you mourn, Padme? Even the greatest ascetic could not resist the attraction of a woman’s beauty. This devilish sultan is, after all, a despicable human. Forget about him. You are blessed with the glow of the sun, my dear! Come, let me hold you in a warm embrace. Enjoy this bliss and forget everything else.’

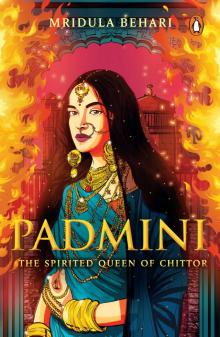

Padmini

Padmini